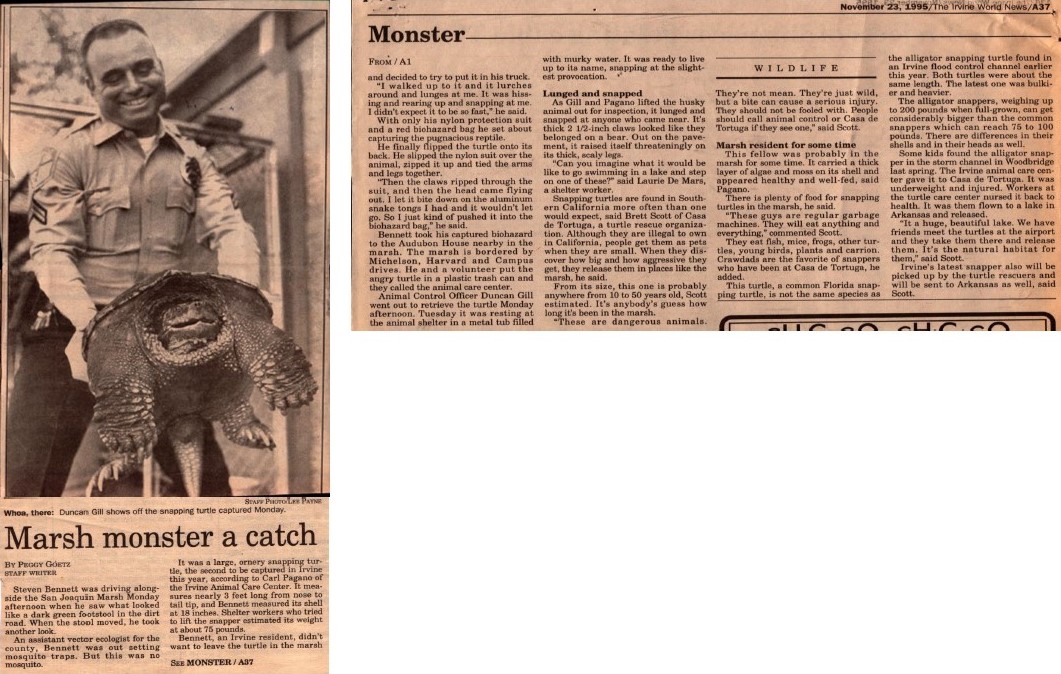

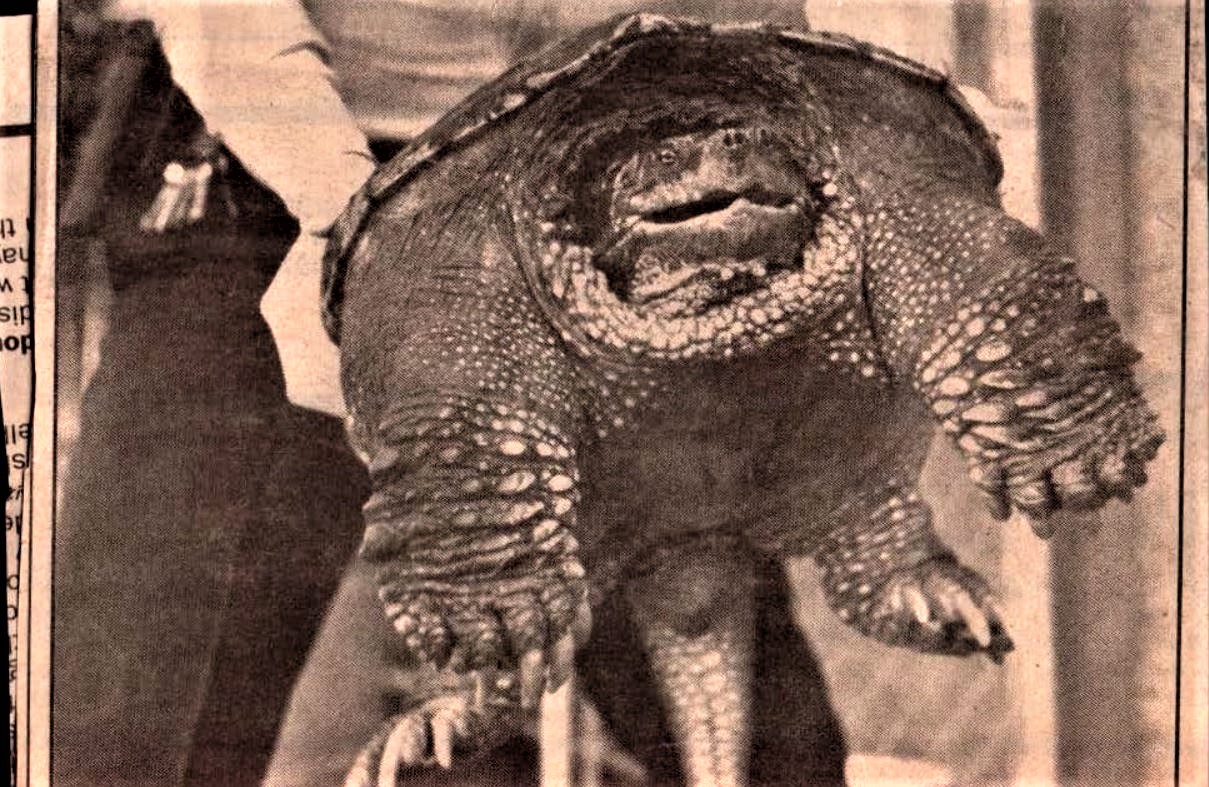

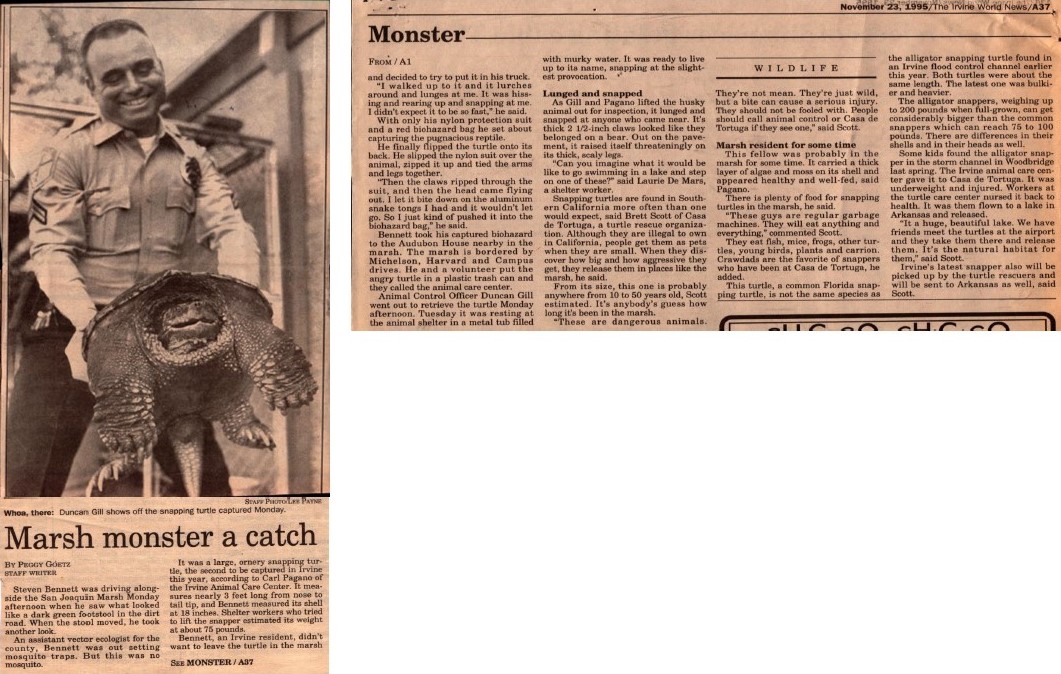

The headline 25 years ago was terrifying: A hissing “marsh monster” — lurching, biting, and finally ripping through a makeshift trap with its bear-like 2 ½-inch claws — was discovered at IRWD’s San Joaquin Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary.

Biologists at the time told the Irvine World News it was a snapping turtle, probably between 10 and 50 years old. The bad-tempered beast was captured and transported to a rescue organization for safe keeping.

Snapping turtles are illegal to own in California, but many people get them anyway when they are small, and release them into the “wilds” of suburbia once they get big — and aggressive.

But it’s not just turtles. A whole host of creatures are living at the marsh. They either found their own way or were brought there by a neighbor.

Wetlands Scientist Mo Wise said she once saw a goldfish swimming in one of the ponds. It was the size of a baseball.

“The marsh is chock full of surprises,” she said.

Other wild and/or non-native animals found there include rabbits, coyotes, raccoons, crayfish, woodrats, exotic birds, many varieties of turtles (including the snapping variety), and fish.

“There are 15 species of fish at the marsh,” said Natural Resources Manager Ian Swift. “None of them is native.”

Apart from the goldfish, Swift and Wise have spotted catfish, bass, red shiners and other species that were either planted there or found their way from upstream.

The fish provide food for the birds at the marsh, as well as the turtles. Despite most of these species being invasive, a healthy balance of life is going on, Swift said.

“There’s this huge food chain that exists at the marsh that wouldn’t be there naturally,” he said. “So far, there’s an equilibrium, where it doesn’t look like there are too many impacts.”

Some of these species are brought in by humans: pet fish and turtles that have outgrown their homes, stray rodents, even a few kittens.

Releasing these orphaned pets and pests is not good — for the animals or the marsh.

Rodents brought in might have ingested poison, which can harm the native birds when eaten as prey. Rabbits nibble away at the native grasses before they can take root. And the turtle population — while currently in balance — can easily get out of hand.

IRWD monitors and records the animals spotted at the marsh for research. It’s another way to keep track of the ecological balance of the wildlife sanctuary, and it helps to identify new changes and trends.

Swift described his occasional encounters with a bobcat mother and her cubs some years ago — walking down the paths between the various ponds. They are still seen from time to time throughout the natural areas of Irvine, but they haven’t visited the marsh since 2015.

“I miss seeing them,” he said, “but at least we know they’re OK.”

If you find yourself with an unwanted pet or animal, please don’t release it at the marsh. Contact your local animal shelter to arrange for a safe surrender.